Based on the 2001 WMAP results, the Universe is flat with a 0.4% margin of error. But what exactly are the chances of the Universe being finite but unbounded? I know it’s an unanswered question in cosmology, but is there any estimate?

The short answer to this question is that the Universe cannot be both flat and closed. (A finite but unbounded universe is typically referred to as a ‘closed’ universe.) Since we are pretty much certain the Universe is flat, the chances of it being closed instead are correspondingly small. To be specific, the most recent measurements (2015) from the Planck collaboration find the Universe is flat to within 0.5%. So, the probability that the universe is finite and unbounded is — roughly speaking — 0.5%.

Exactly why the Universe’s flatness precludes it from also being finite and unbounded is a bit more subtle, and requires a precise understanding of what we mean when we say the Universe is ‘flat’, ‘finite’, or ‘bounded’. As we’ll see, all three are related but refer to slightly different things:

Bounded: This is the most straightforward of the three. Something is bounded simply if it has an edge. The surface of a table for example, is bounded (also finite and flat, but we’ll come back to those later). The surface of the Earth, on the other hand, has no edge and thus is unbounded: regardless of what direction you choose to walk, you will eventually end up back where you started. (In reality this is the farthest you can walk in a straight line without drowning.)

While this is easiest to comprehend in two dimensions, the same holds true for three dimensional spaces. For example, the interior — as opposed to the surface — of the Earth is a bounded 3D space, while an infinite universe is unbounded.

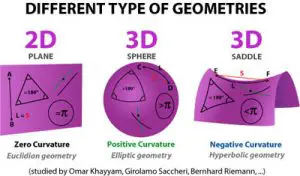

Flat: When we talk about the flatness of the Universe, we are using the term in its most general geometric sense. A flat space is simply one in which geometry is Euclidean; i.e., that parallel lines remain parallel forever, the sum of the interior angles of a triangle is always 180 degrees, and the circumference of a circle is always 2π times the radius. In contrast with its colloquial meaning however, flatness does not imply anything about the dimensionality of a space. We can talk about a flat 2D space, a flat 3D space, even a flat 4D space. A sheet of paper, for example, is a flat 2D surface, and remains flat whether you roll it into a cylinder, or fold it into an origami swan, no matter how you bend it in 3D space.

The surface of the Earth on the other hand is an example of a curved 2D surface. Look at the diagram above: each surface has a triangle drawn on it (just three straight lines that intersect), but only on the 2D plane surface will the angles add up to 180 degrees. The other two — the sphere and the ‘saddle’ — are examples of curved surfaces.

Now — and this is where things get weird — you can also have curved 3D space. (What does it curve into?!) Unfortunately our puny human brains are ill-equipped to comprehend this, as it requires the ability to conceptualize a 4th dimension, something our everyday experience leaves us quite unprepared to handle. Be that as it may, curved 3D space is one of the central tenets of general relativity: matter curves the space around it, and the curvature of the space then controls how the matter moves. This is why you feel as if you aren’t moving even though the Earth is orbiting the Sun at 65,000 miles per hour: just like a car on the highway, the Earth is moving in a straight line; space itself is what’s curved!

Finite: At first glance finiteness is a relatively straightforward concept, defined simply as something that is not infinite. (Infinity is a tricky concept though.) While this definition is frustratingly recursive, an infinite space is best described as boundless (or unbounded). So any infinite space is also unbounded, in the sense described above. Simple as that. By extension then, any bounded space must be finite. However, you can also have a finite, unbounded space! Think about the surface of the Earth again: clearly finite, but also unbounded. Trick is, it can only have both of these properties if it also has what is know as positive curvature (the sphere in the image above, as opposed to the saddle).

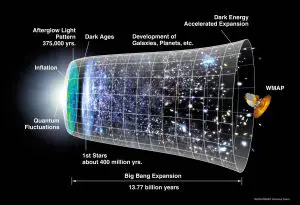

Now that we’ve thoroughly defined those terms, let’s look at how they apply to the Universe. Cosmology (the study of the origin and evolution of the Universe) rests on two fundamental assumptions. One is the Copernican Principle, which states that the Earth, Sun, Milky Way, etc. do not occupy a special place in the Universe. The other is the Cosmological Principle, that on sufficiently large scales, the Universe is homogeneous (looks the same no matter where you are) and isotropic (looks the same no matter where you look).

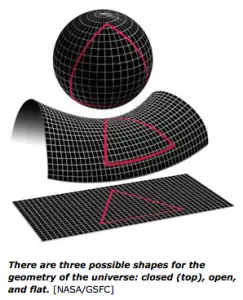

These principles lead to a third assumption cosmologists make about the Universe: that it is unbounded. This doesn’t necessarily mean the Universe is infinite, just that if it isn’t, it also has to be curved! General Relativity actually allows for three possibilities:

- A finite unbounded universe — called a ‘closed’ universe

- An infinite flat universe

- An infinite curved universe — called an ‘open’ universe

As it turns out, the general shape the Universe takes depends on the total amount of ‘stuff’ in the Universe, both matter and energy. The more stuff there is in the Universe, the more curved space is, with a flat universe just being the dividing line between a ‘spherical’ finite universe and a ‘saddle-shaped’ infinite universe. Up until the past few decades we didn’t really know which category the Universe fell into. Recently though, precision cosmology satellites like COBE, WMAP, and Planck, combined with ground-based observations have allowed us to very carefully measure the geometry of the Universe. And so far, it looks like the Universe is exactly flat, within a 0.5% margin of error.

Jacob Hummel

UT Austin