If X-ray and radio beams can emit from black holes and the like in interstellar space, can lower frequency waves on the middle to low end of the spectrum be emitted from high-powered beams on Earth and then detected by telescopes – like a sub pinging to its target – in order to search for exoplanets and life outside Earth?

This is a great question, which I believe a lot of people have thought about. To answer this question, I would like to first discuss the origin of the X-ray and radio emissions and the signatures of exoplanets and extraterrestrial life (life forms residing outside of our Solar System). Then we can think about how to detect exoplanets and extraterrestrial life with telescopes or other facilities.

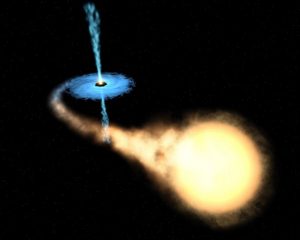

The X-ray and radio emissions from black holes are actually emitted from accretion disks around black holes. So what is an accretion disk? A black hole is an extremely dense object whose gravitational force is so strong that light cannot escape from it within a certain radius (also called the Schwarzschild radius). Since no light can escape from the black hole itself, we cannot detect “the light emitted from black holes” with telescopes. However, beyond that radius, matter such as gas and dust can survive and be detectable. The surviving gas orbits around black holes just like the Earth orbiting around the Sun. Because there are numerous gas particles orbiting around the black hole, it forms a disk, whose inner rim is constantly accreted by the black hole, therefore called accretion disks.

The gas particles in accretion disks moves violently due to the steep change of gravitational force with the distance to black holes. The violent motion results in friction between any two nearby gas particles, releasing heat, and in the end very high temperature in accretion disks (about a million Kelvin for supermassive black hole, the black hole at the center of galaxies). Atoms in such high temperature become ions and release their own electrons. Those free electrons interacts with each other, emitting free-free emission (thermal bremsstrahlung emission) in X-ray.

On the other hand, radio emission originates from interactions of electrons and strong magnetic field induced by the motion of ions in accretion disks. Electrons spiral around magnetic field lines and emit radiation in radio wavelength (also called synchrotron radiation).

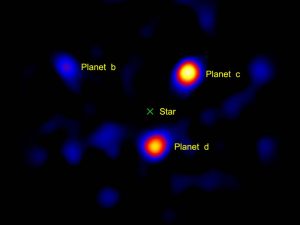

Unlike black holes, whose signatures can be easily detected by their own emission, exoplanets are mostly identified by indirect methods. There are three major identification methods: radial velocity, transit, and direct imaging. All of them involve observations of the variation of light (mostly in visible and near-infrared) over time. The method of radial velocity measures the wobbling of the planet-hosting star due to the gravitational perturbation from planets. A transit event occurs when the planets cross in front of the star, just like a lunar eclipse when the Moon blocks the sunlight. Planet Hunter is a website where anyone can help identify planets based on their transit events (http://www.planethunters.org/). Finally, direct imaging is simply taking an image of planets directly; however it is challenging because planets are usually very small compared to stars, and they are also very faint. All three methods are widely used nowadays by astronomers to determine the properties of exoplanets, such as their orbital periods, the size of their orbits, their masses and their radii.

So now we know how to find a planet, but how do we know whether there is life on the planet? The primary way is to examine whether a planet has the conditions that are suitable for life. According to our only reference of the conditions for life, our Earth, astronomers usually look for rocky planets orbiting around its host star at a distance comparable to the distance between the Earth and the Sun (1 AU). Those are the general conditions which we believe that any life form would need, a solid planet (not a gas giant like the Jupiter) with liquid water. There are many astronomers dedicating their career to hunting for planets in the habitable zone and characterizing them.

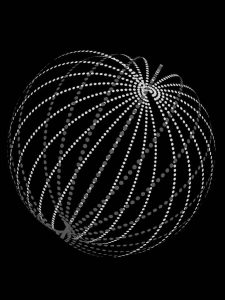

However, a suitable condition for life does not mean that there will be life. Direct detection of extraterrestrial life is much more difficult to achieve and confirm. This is a two-fold question: what constitutes direct evidence of life, and then how do we detect it? According to Wright et al. (2014), there are two main ideas for direct detection of extraterrestrial life. First, if another intelligent civilization has developed a similar communication technology to ours, it is likely that we can intercept their signal, which may be intentionally or unintentionally pointed toward us. Second, any artificial signatures in the signal of exoplanet detections can be the evidence of life activities. Dyson (1960) proposed the idea that a civilization will be interested in collecting more and more energy for its rapid development; therefore, it will try to build a structure to intercept as much of the radiation from its host star as possible, resulting in a “sphere” around the star called “Dyson sphere.” Such a structure will not be necessarily a complete sphere. The signal of Dyson sphere may be detectable from radial velocity or typical methods for searching exoplanets. But we have not yet found any direct life evidence.

The second-part of the mission of detecting direct signatures of life is how to detect them. In general, we can emit radiation from the Earth to an exoplanet like you suggest and then analyze the reflected signal for any perturbation caused by extraterrestrial life, and there is another way which we simply search over the sky for any life signature.

There are several issues with actively searching for life using the method described in your question. The first one is the amount of energy needed. The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), the most powerful radio antenna array in the world, can detect a signal of 10 millionth Jansky. A Jansky is an unit of energy density per unit area that astronomers usually use because the amount of energy we receive is much smaller than we encounter in our daily life. A Jansky is about 10-26 Watts/Hertz/meter2. With the tiny beam of ALMA, we can collimate the beam within 0.1 arcsec (about 0.005% of the size of the Moon). If we want to send a signal to the closest star (assuming it has planets), alpha Centauri, at a distance of 4.37 light year, our beam will be 28 solar radius wide when arriving alpha Centauri compared to the Earth diameter of 0.02 solar radius. Therefore, if there is a planet orbiting around alpha Centauri, only a millionth of the beam will be actually on the planet. Then, the radiation reflects back toward us. In the end, it would require about 50 million Watt, about 10% of the power of a nuclear power plant. So the required energy is enormous (but not totally impossible).

The second obstacle, also a major problem, is what signature of life we can actively detect. If we could receive the signal back from the planet we pinged, we would still have to analyze the difference between the original signal and the received signal caused by civilizations and many other factors, such as planet atmosphere, interstellar medium, and our atmosphere. Those other factors make the detection of life almost impossible unless there is a distinct feature only related to extraterrestrial life, which we have not found it yet. Thus, astronomers look for signatures of extraterrestrial life by analyzing the spectra and images of exoplanets and elsewhere instead of actively emitting signal toward them.

In the end, the short answer for your question is that it is unlikely that we can actively emit radiation to look for exoplanets or extraterrestrial life. The received emission would be either too faint or confused by other astrophysical processes. Nowadays, astronomers use various methods to detect exoplanets directly or indirectly and have a promising progress in the past decade. As we learn more about exoplanets, we are closer to knowing how life started on Earth and whether there is life out there.

Reference:

- Wright et al. (2014): The Ĝ Infrared Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies

Best,

Yao-Lun Yang

UT Austin